Our Lakes : Connecting the Dots.

Artistic Statement:

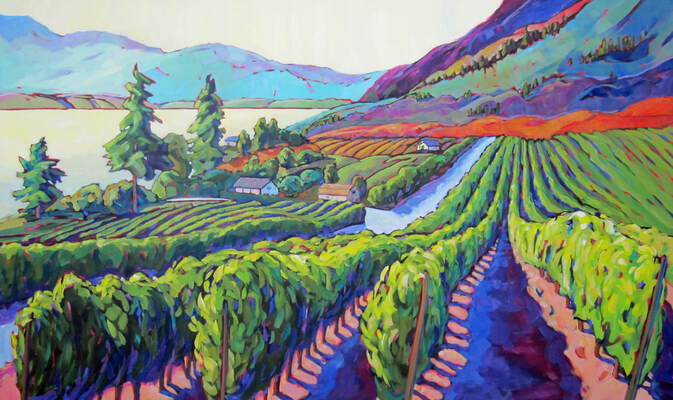

What does “Our lakes: Connecting the dots” means? First, it’s about our lakes. The Okanagan basin lakes. These incredibly beautiful lakes and the creeks and rivers that regulate their levels. “Our” lakes because it’s not good enough to live here or visit the area and just enjoy looking at them. It’s another one of those privileges that comes with responsibilities. So, by saying “our” everyone can feel a bit of that connection which entails and demand care and stewardship.

“Connecting the dots” is born from the obvious connection that each lake has with its neighbors. What affects one lake will undoubtedly impact the others. But just as the animals, the vegetation, all living things within the geography of the area are all connected in a working ecosystem, there is another level of connection. That one has to do with our own connection to the lakes and to that ecosystem as well as each other. So many individuals who dedicate their time and efforts to work with others in order to keep these beautiful lakes as clean and productive as they can possibly be.

So this art show is about celebrating the beauty of the lakes within the Okanagan watershed but also celebrating the vision and positive impact that many groups have on the lakes. These groups are part of a network that connect them to each other’s and to the lakes. This is what I mean by it. Let the art and the beauty of this area inspire you to read about and join these groups in their efforts to make a difference every day. “Harnessing the power of Art to promote conservation”

What does “Our lakes: Connecting the dots” means? First, it’s about our lakes. The Okanagan basin lakes. These incredibly beautiful lakes and the creeks and rivers that regulate their levels. “Our” lakes because it’s not good enough to live here or visit the area and just enjoy looking at them. It’s another one of those privileges that comes with responsibilities. So, by saying “our” everyone can feel a bit of that connection which entails and demand care and stewardship.

“Connecting the dots” is born from the obvious connection that each lake has with its neighbors. What affects one lake will undoubtedly impact the others. But just as the animals, the vegetation, all living things within the geography of the area are all connected in a working ecosystem, there is another level of connection. That one has to do with our own connection to the lakes and to that ecosystem as well as each other. So many individuals who dedicate their time and efforts to work with others in order to keep these beautiful lakes as clean and productive as they can possibly be.

So this art show is about celebrating the beauty of the lakes within the Okanagan watershed but also celebrating the vision and positive impact that many groups have on the lakes. These groups are part of a network that connect them to each other’s and to the lakes. This is what I mean by it. Let the art and the beauty of this area inspire you to read about and join these groups in their efforts to make a difference every day. “Harnessing the power of Art to promote conservation”